Puerto Princesa City Tour: A visit to Plaza Cuartel, Iwahig Firefly and Iwahig Prison

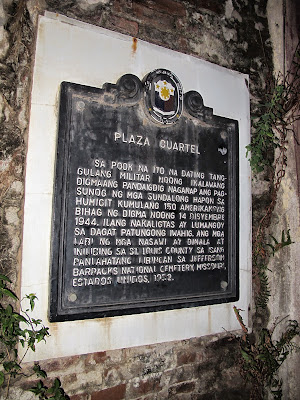

Plaza Cuartel. Sa pook na ito na dating tanggulang militar noong ikalawang digmaang pandaigdig naganap ang pagsunong ng mga sundalong Hapon sa humigit kumulang 150 amerikanong bihag ng digma noong 14 Disyembre 1944. Ilang nakaligtas ay lumangoy sa dagat patungong Iwahig. Ang mga labi ng mga nasawi ay dinala at inilibing sa St Louis County sa isang pangkalahatang libingan sa Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery, Missouri, Estados Unidos, 1952.

***

Plaza Cuartel.

***

Plaza Cuartel.

***

The commemorative marker with the sculpture of Don Schloat, an American veteran

and was once a POW in Palawan.

***

Valley Center artist Don Schloat is a World War II veteran who recently dedicated a memorial in the Philippines to 139 American POWs massacred by their Japanese captors Dec. 14, 1944. Prisoners at the camp, on the island of Palawan, were killed when the Japanese thought the island was being retaken by Allied forces.

***

This blogger shall quote the article from the above link, entitled, Veteran won’t let massacre be forgotten: Memorial created at Philippines site.

VALLEY CENTER — Soon there will be no more witnesses to what occurred on the Philippine island of Palawan on Dec. 14, 1944, when Japanese captors massacred an estimated 139 Americans in one of the most horrific episodes of World War II.

But Don Schloat, a Valley Center artist and veteran who was a prisoner at the camp before the mass murder there, was the driving force behind a new memorial at the site of the killings. With the help of the municipal government of Puerto Princesa City, Palawan’s capital, a permanent monument now graces a city park to honor the men who were slain on that day 65 years ago tomorrow.

The massacre has haunted Schloat, 88, for decades. Ten years ago, he completed a series of 77 paintings that depict the slaughter in abstract, impressionistic and realistic forms. It was a gruesome but cathartic enterprise. The paintings have been exhibited over the years in the San Diego area, and today all but one are on permanent display in Santa Fe, N.M.

Schloat said that by March, he had concluded that without his personal efforts, a memorial probably would never be built at the site of the massacre. He said he had thought about the need for a memorial in Puerto Princesa City for years.

“You would think the United States would have done it instead of a private individual, but they haven’t,” Schloat said last week. “I’ve been waiting for our government to do a monument, to do something, so they wouldn’t have died in anonymity.”

Schloat traveled to the Philippines a handful of times earlier this year, meeting with officials from the city government. He paid a local architect a few hundred dollars to design plans, and during a trip to Puerto Princesa City in September, the monument was finally built.

Schloat had originally planned to pay for the monument himself, but the mayor of Puerto Princesa City, Edward Hagedorn, used city funds to pay for the supplies and a crew to construct it.

The site of the massacre actually has had a small monument that displays the names of the handful of survivors — Schloat’s name is mistakenly included — but there had been no official memorial to those who were killed.

The new one is a simple obelisk with bronze faceplates that tells the story of what happened and bears the names of the men who died there. A bronze statue created by Schloat sits atop the memorial. It depicts a tortured male figure writhing in pain as flames rise from his feet.

Schloat had been an Army medic at Bataan before being imprisoned at Palawan early in the war. Nearly two years before the massacre, Schloat tried to escape but was quickly captured and sent to Bilibid, a POW camp in Manila.

He spent the rest of the war there, racked with dysentery, beriberi, pellagra and scurvy. He learned of the massacre after he was liberated Feb. 4, 1945.

Eugene Nielsen, now 94 and living in Ogden, Utah, was one of 11 survivors of the massacre. Captured after the fall of Corregidor on May 6, 1942, Nielsen was sent to a prison camp at Cabanatuan, north of Manila, and then to Palawan. There, he and 300 other prisoners were forced to build an airfield in stifling heat. Random brutality was common on Palawan as the men crushed rock and coral to build the airfield.

By late 1944, half the men at Palawan had been transferred to other camps, leaving about 150 POWs.

In December, U.S. planes were attacking the island, dropping bombs on the uncompleted runway, Nielsen said.

About noon Dec. 14, shortly after two American P-38 fighters flew overhead, the Japanese guards yelled at the Americans to get into earthen air-raid shelters.

They immediately poured gasoline over the shelters, set them afire and tossed grenades inside. Men scrambled out only to be bayoneted to death, Nielsen said.

Nielsen, at one end of a shelter, struggled outside and in the mayhem hid in a pile of garbage for several hours before diving through a barbed-wire fence, over a cliff and into the ocean — getting shot several times as he escaped. He estimates he swam for eight miles before meeting up with Filipino guerrillas.

“I just couldn’t quite believe that people, that any human, could be like that,” Nielsen said last week of the brutality of his captors.

Today, the monument represents not only a part of American history, but Philippine history as well, Schloat said.

“The monument tells the story of what happened there, and that will go on for generations, as long as granite and bronze lasts,” he said.

Bruce Lieberman: (760) 476-8205; bruce.lieberman@uniontrib.com

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

Comments

Post a Comment